Many years ago, on an Alaskan ferry heading for Sitka, we heard an announcement boom out over the top deck. The captain announced a summer-season treat–a free nature talk given by a young university student. We gathered around her in the sheltered lounge. The signboard said her talk was about “The creature that loses its head.” We were intrigued!

Turns out, she was talking about the life cycle of the acorn barnacle! If you’ve ever walked in the intertidal zone along the coast of Vancouver Island, you probably noticed clusters of off-white hard-shelled forms gathered in large and small patches on the surface of the rocky shore. Barnacles are crustaceans, similar to crabs and lobsters; they have a hard exoskeleton, they molt, and have segmented limbs (the ‘cirri’ or jointed legs they use to capture food in the water).

Unlike many other crustaceans, adult barnacles are sessile and live in a castle-like structure made up of six calcerous plates, each plate standing up like a shield on end. The top or crown is usually closed during the day (with a hinged “lid” made of two overlapping plates). If you were lucky to see them when the tide was coming in, you may have even seen the top open, and delicate fronds (the legs) extending to search for food.

The young lady in a ferry worker uniform passed around handouts and began her story Baby barnacles are born from eggs. Barnacles are hermaphroditic (they possess both male and female reproductive organs. They typically reproduce through cross-fertilization, exchanging sperm with nearby barnacles. This strategy maximizes genetic diversity.The eggs mature within the shell and form tiny, translucent creatures that leave to swim in the ocean.

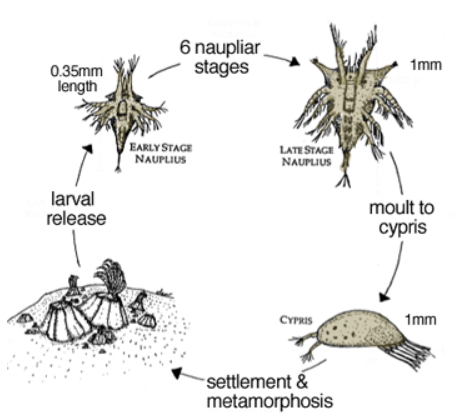

These swimming larvae (Nauplius larvae) have a single red eye, a head, and a pair of limbs. They molt six times and eventually develop an additional eye, a cement sac near the eyes, and stop eating (no mouth). Each larva forms a “helmet” or hard shell and begins looking for a place to call home (they are now Cyprid larvae).

When a Cyprid finds a suitable hard surface, it exudes a cement-like substance and sticks its helmeted head to its new home (thus “losing its head”). The juvenile begins a metamorphosis as it builds the encasing plates and its “legs” modify to become the filter-feeding fronds that extrude from the open plates at the top of their shells. The adult is now permanently encased although it does grow and sheds its skin regularly, pushing it out the top mantle. It is thought that it may also make more room by producing a substance that periodically erodes the inner calcerous plates.

An amazing story of multiple changes and a complex life cycle. I still find it hard to understand how this convoluted and arduous process of growth from egg to adult ever evolved – can you?

Want to learn more about barnacles?

- Royal BC Museum: Barnacles of BC

- Barnacles of BC: Barnacles Atlas

- Snail’s Odyssey: Crustacea-Acorn barnacles

- Hakai Wild – Vimeo video: Under the Dock: Barnacles

- Hakai magazine – Peeking into the Ocean (photos of nauplius larva) and

- “Species of the Day” lichen on a barnacle